|

|

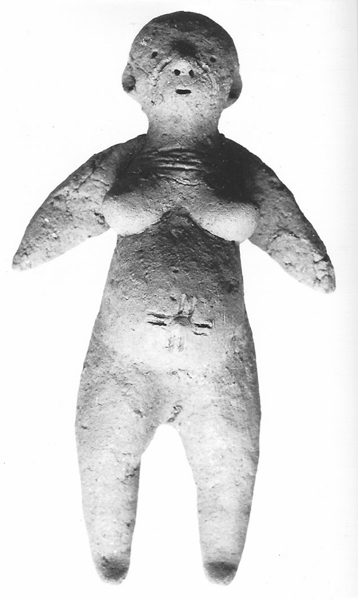

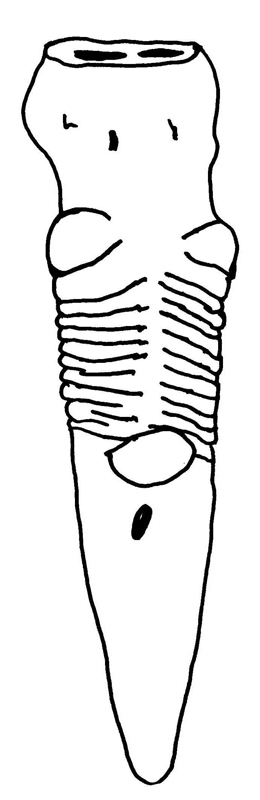

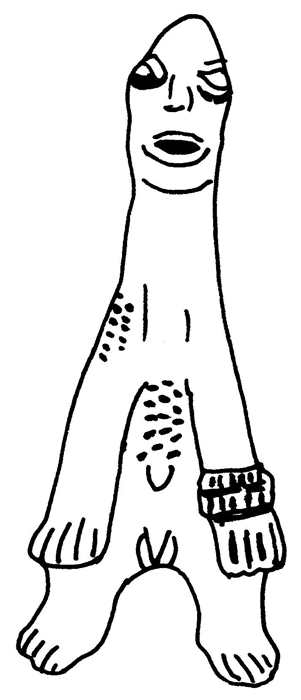

Fig. 1. Bulsa doll |

Franz Kröger

Scarification and Labrets

|

|

Fig. 1. Bulsa doll |

Many ceramic or wooden sculptures of

West Africa are characterized by a strong stylization of the human body. Details

such as fingers, toes and ears are often altogether absent, and even the arms

are indicated by only short stubs. Examples of this kind are the so-called

wooden Mossi dolls or the small clay figurines of the young shepherds of

Northern Ghana (Fig. 1) . The corresponding tribal and/or ornamental marks are, however,

almost always applied in detailed form. Among the terracottas of the Niger

Inland Delta (Djenné, Bankoni), ornamental scars are plentifully represented on

almost every part of the body. Although the Komaland terracottas show certain

affinities with those of the Niger Inland Delta in other formal elements,

relatively few marks can be identified as scarifications with some degree of

certainty. The categorical assertion by Beltrani (1992. 431, footnote) that the

Komaland figures have no scarifications is, however, not tenable.

With respect to their excavated figures, Insoll / Kankpeyeng / Nkumbaan mention

the occurrence of putative scarification marks on the feet, arms and shoulders

(2012: 35f). Kankpeyeng surmises that an excavated iron knife may have been used

for scarification, circumcision, and surgery (2011: 3).

Facial scars

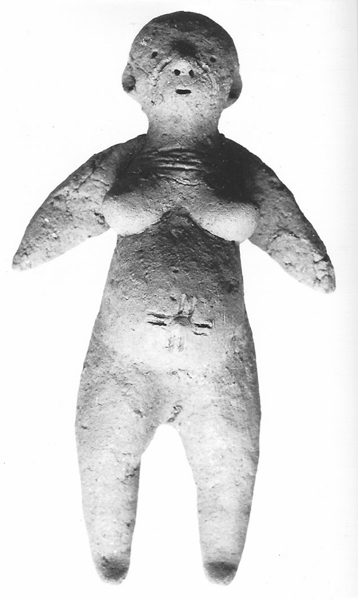

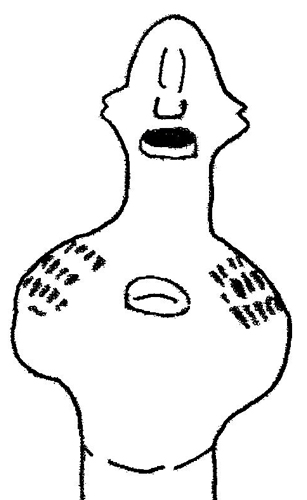

Facial scars which may have served as tribal marks can, to my knowledge, only be

found on a figurine excavated by James Anquandah (1985: 16; Fig. 2). Two scars

each extend from its nose and across the cheeks.

|

|

Fig. 2. (according to Anquandah 1985:16) |

In this form they correspond exactly to the tribal scars as they are (or were) worn by the Bulsa (Kröger 1987. 118ff) as well as other ethnicities of Northern Ghana (Armitage 1913). As part of a more widespread facial scarification phenomenon, they even occur on Nok terracottas (B . Fagg 1977, Fig. 24, 25, 57, 62).

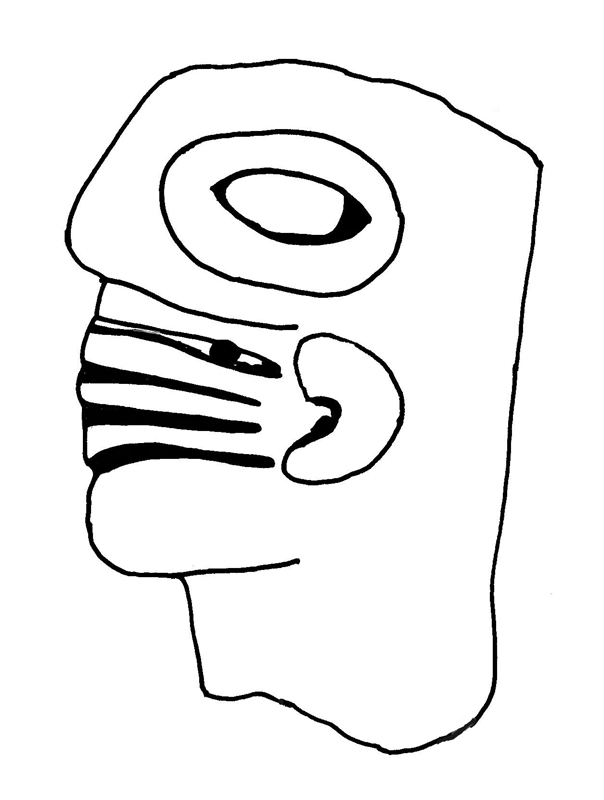

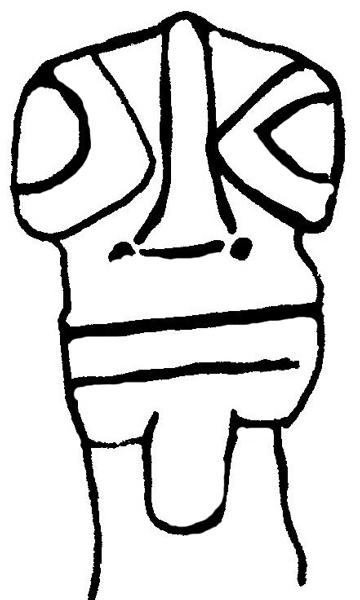

On a Komaland terracotta head (Fig. 3), two grooves even with the mouth extend across the entire face from ear to ear. The upper groove includes the two nostrils while the bottom groove includes the mouth. Although facial scars begin at the corners of the mouth among some groups of the present-day northern Ghanaian people, the importance of the terracotta grooves remains a mystery. The bottom groove could be interpreted as a stylized extension of the mouth, but for the top one, there is no obvious explanation.The representation described here

|

|

Fig. 3. |

could be compared with those of the sculptures of Fig. 4-6, on which five or more parallel grooves between the nose and chin are perhaps intended to represent multiplied lips.

In a figurine of the Manchester exhibition (Catalogue: 2013: 16 and 17), six coils around the head are situated between the nose and chin. The editors interpret this depiction as a "bound mouth" which perhaps indicated that the status of the person portrayed was that of a prisoner or slave. It is difficult to decide whether this figurine with coils instead of grooves expresses a similar phenomenon to those described above.

|

|

Fig. 4-6 |

Rectangular patterns on the temples

|

|

Fig. 7 |

Several West African anthropomorphic

sculptures depict rectangular scar ornaments between the outer corners of the

eyes and the ears (Fig. 7). Quite often we find them on the clay figures of the Niger

Inland Delta as well as on the wooden sculptures of the Dogon / Tellem and Akan

but less often on the Komaland terracottas. Here the rectangle in bas-relief is

provided with horizontal and/or vertical incised lines.

Thoracic and abdominal scars

|

|

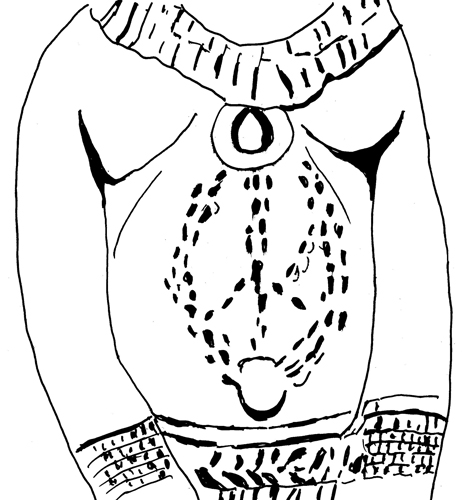

(From left

to right) Fig. 8. Komland terracotta, Fig. 9. Lobi scarification

(Meyer 1981: 55), Fig. 10. (Fisher 1984: 110) |

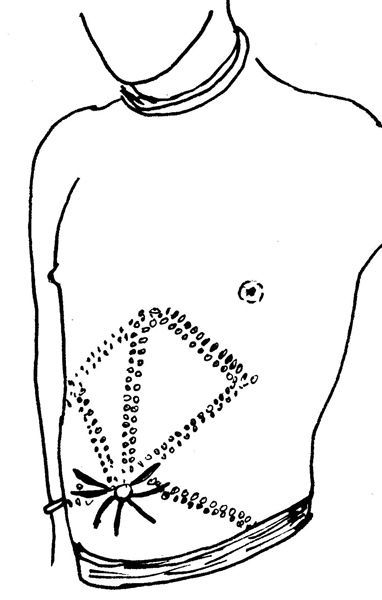

Representations of belly scarifications occur among the Komaland

terracottas, though rarely on male and female figures.

|

|

Fig. 11 |

A very elaborate pattern of scars

that range from the navel to the breasts of a female figure (Fig. 8) has

similarities with the belly scarifications of a Lobi man as depicted by P. Meyer

(1981: 55; made on the basis of an old photo in 1934, Fig. 9) as well as with those

found on a Sara woman from the Chad area (Fisher 1984: 110; Fig. 10). A

commonality to all three representations is an elliptical or diamond-shaped

pattern composed of small point-like or elliptical scars. This pattern is

divided into two parts by vertical rows of scars. In other Komaland figures , the abdominal scarifications consist of only 2 to

3 vertical rows of small incisions (Fig. 11). Radial incisions around the navel, as they

are typical of northern Ghana today, could not be observed on any figure of the

Komaland terracottas.

Scars on arms and shoulders

|

|

Fig. 12 |

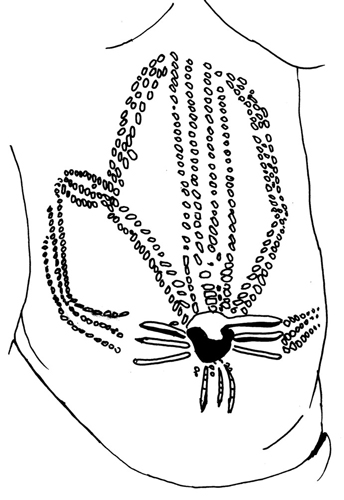

In addition to the face and abdomen,

shoulders and upper arms were also a place for scarifications. On a male figure

(907Z) the same type of incisions found on the right shoulder can be found on

the abdomen. In other figurines (Fig. 12) similar incisions appear in three rows

on both shoulders and upper arms.

In addition to the incised marks, knob-like or elongated button scars were also

represented on the shoulders (427Z), but it is not clear if they really

represent button scars or rather boils.

Labrets

|

|

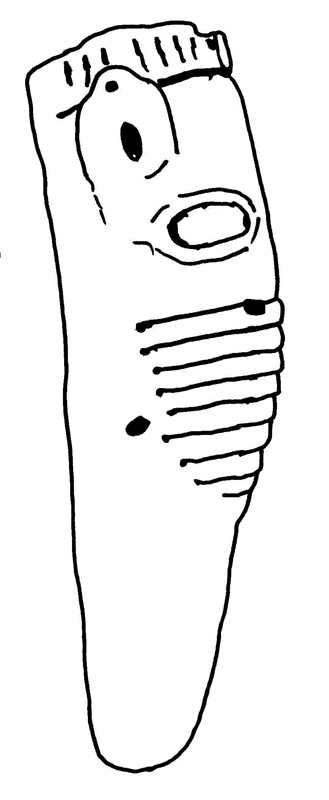

Fig. 13 |

In the booklet about the Komaland Exhibition in Manchester (2012: 33), a small flat cylindrical quartz plate which the authors call lip or ear-plug is depicted. This interpretation can be agreed with, because Northern Ghanaian Lobi women are also represented with similar labrets above the upper lip and below the lower lip in the works of Rattray (1932, Fig. 113 and Fig. 114). On the terracotta figures, such facial ornaments could not be clearly demonstrated. It is not evident whether the representation shown in figure 932Z and 8397 should be interpreted as a labret, the chin or the beard of the head (Fig. 13).

References

Anquandah, James (1987)

L'art du Komaland. In: Art d'Afrique Noire, 62 : 11-18.

Armitage, C.H., 1924

The Tribal Markings and Marks of Adornment of the Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast, London, Royal Anthropological Institute.

Fagg, Bernhard 1977

Nok Terracottas. Published by Ethnographica for the National Museum, Lagos.

Fisher, Angela 1984

Afrika im Schmuck. Köln: Dumont.

Kröger, Franz 1978

Übergangsriten im Wandel. Kindheit, Reife und Heirat bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana, Kulturanthropologische Studien, eds. R. Schott and G. Wiegelmann, vol. 1, Hohenschäftlarn.

Insoll, Timothy, Benjamin W. Kankpeyeng and Samuel N. Nkumbaan 2012

Fragmentary Ancestors? Medicine, Bodies, and Personhood in a Koma Mound, Northern Ghana. In: K. Rountree, C. Morris and A. Peatfield (eds.), Archaeology of Spiritualities, New York: Springer, pp. 25-45.

Insoll, Timothy, Benjamin Kankpeyeng, Samuel Nkumbaan and Malik Saako 2013,

Figurines from Koma Land, Ghana. Fragmentary Ancestors. Manchester (Exhibition Catalogue).

Kankpeyeng, Benjamine 2011

Archaeological Field Research in Yikpabongo, Koma Lande, Northern Region, Ghana, January 2011.

Kr

öger, Franz 1978Übergangsriten im Wandel. Kindheit, Reife und Heirat bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana, Kulturanthropologische Studien, eds. R. Schott and G. Wiegelmann, vol. 1, Hohenschäftlarn.

Meyer, Piet 1981

Kunst und Religion der Lobi. Zürich: Museum Rietberg.

Rattray, R.S. 1932

The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland, 2 vols., Oxford.